Every pet lover knows that the relationship we have with our dogs is a deep one, as complex and layered as the relationships we have with fellow humans (and oftentimes more so!) Human-Animal Relationship Awareness Week looks at this relationship from a scientific perspective, helping us to understand the important and ever-changing role that pets have played through the years.

When is Human-Animal Relationship Awareness Week?

Human-Animal Relationship Awareness Week is held Nov. 13-19, 2022. It is always scheduled for the second week of November. Share photos celebrating this special bond with hashtag #HARAWeek.

This pet awareness week was launched in 2016 by Animals & Society Institute, a nonprofit human-animal relationship think tank that is devoted to advancing human knowledge to improve animal lives. ASI is the publisher of Society & Animals and Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science.

The Changing Role of Animals in Our Lives

ASI explores the changing roles that animals have played in our lives through the centuries–and looks at the question of why we keep pets in this guest post:

Why We Keep Pets

Not everyone loves pets. Many people do not like companion animals—they can be messy, can cause great inconvenience, can exacerbate allergies, and many people think all animals should live outdoors. People can get hurt, or even killed, from pets—some exotic pets carry diseases like salmonella, and every year, people die from being attacked by dogs. Many people have pets, but do not elevate them to the status of family members, and others still are concerned about how much money, time, and energy are spent on animals.

It wasn’t that long ago that pet-keeping was seen as so wasteful and irrational that scholars came up with a number of theories to account for the existence of pets. For instance, Konrad Lorenz and other animal behaviorists thought that pets were simply “social parasites:” they have evolved with very cute faces and bodies intended to trigger a parental response in humans.

A related idea is that we anthropomorphicize pets—projecting onto them our own thoughts and desires, and creating in them a form of substitute kin. The idea here is that people who develop attachments to animals are incapable of forming relationships with other humans, so we create artificial relationships with substitute people, or pets. There were even two studies conducted in the 1960s and 1970s that purported to show that people kept pets because they were psychologically unhealthy, and that pets kept their guardians from forming effective social relationships with other people. (Modern research has demonstrated that these studies were extremely flawed.) Today, however, most scholars grant that people with live animals for a much simpler reason—because it provides concrete benefits to us.

Research in the human-animal bond shows that living with animals gives people very real emotional, psychological, and even physical benefits. Finally, the Victorian motivation for owning pets—to teach children positive skills such as kindness and empathy—is still a factor today. Studies indicate that forming attachments to companion animals may develop nurturing behavior in children, and children with pets may exhibit more empathy than other children. But the number one reason that people keep pets today is companionship.

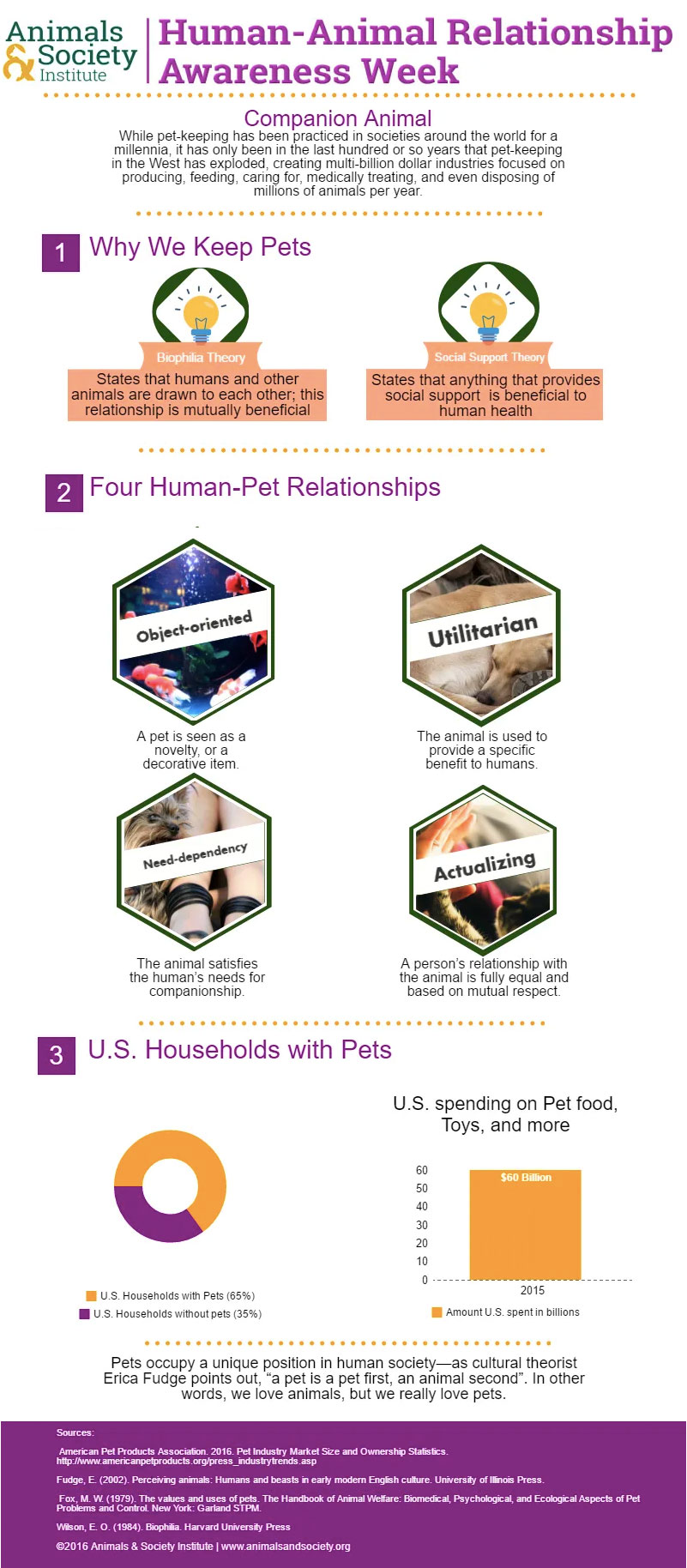

Scientists have developed a few theories to try to understand why humans benefit so greatly from living with companion animals. The biophilia hypothesis, introduced by biologist Edward Wilson (i), states that humans and other animals are naturally drawn to each other, and that this relationship is mutually beneficial. This explains not only the human-companion animal bond, but also why animals play such a strong role in the literature, art, and games of children.

Another explanation suggests that humans are hard-wired to pay attention to animals since for much of human evolution we depended on them as a source of food. In other words, the interest in animals as pets is only secondary to our interest in animals as food.

A different theory is known as the social support theory, and states that anything that provides social support (such as marriage, belonging to a church, or membership in a social club) is beneficial to human health because of our need to have social contact. Whether that contact is with animals or other humans is irrelevant—the point is that we have social contact with another creature.

And finally, some scholars suggest that since men tend to have more social support than women do, women may need companion animals more than men.

The Human-Pet Relationship

Companion animals have a “social place” in our family, household, and daily routines. By incorporating them into our breakfast-eating, TV-watching, and holiday-taking routines, they are truly a part of the family.

The human-pet relationship is different from most every other human-animal relationship, in that it is not based primarily on utility, and in that it is truly a two-sided relationship, in which both parties—human and animal—play a major role.

When we interact with a companion animal, we are interacting with an animal who we know as an individual, and whose purpose in our lives is one of companion, friend, and even family member. In the most ideal circumstances, the relationship is structured not simply by the human’s needs or interests, but by the animal’s as well.

One of the most important criteria for being a pet is having a name, because having a name symbolically and literally incorporates that animal in the human domestic sphere. Having a name also allows for human-animal communication: we can talk to animals.

While non-human animals do not possess human verbal language, we can and do still talk to them, and many companion animals understand much of what we say, based on our tone, inflection, body language, and facial expressions, and many animals know the meanings of specific human words, including, but not limited to, their names.

Sociologists who have studied human-animal communication have shown that like baby talk, human-pet communication has a clear structure, and, as well, a distinctive tone, set of bodily gestures, and comportment. Beyond immediate communication, this talk serves as a sort of glue in human-animal relationships and, more broadly, enhances the social lubricative function of companion animals in human-human relationships. Sociologist Clinton Sanders (ii) has studied the communication between humans and dogs, and maintains that language enables human and canine interactants to construct and share a mutually defined reality.

Animals, because they lack human language, are normally excluded from social exchange with humans, but in the domestic realm, guardians of pets have made a number of allowances for that lack of language. Ask any caretaker and they will not only admit that they talk to their animals, but they will maintain that their animals understand what they are saying.

In addition, we speak “for” our animals—to friends, to family, to the veterinarian. We also speak through them; sometimes people use their pet dog or cat as a sort of mediator to communicate information to another person.

Pet owners see cross-species communication as real and possible, and this possibility itself allows for that communication, and for the reciprocal relationships that we have developed with our companions. By opening up the door to cross-species communication, and by including (some) animals in our own worlds, we humanize those animals, giving them a “person-like” status.

Not all people relate to companion animals in the same way. Psychologist Michael Fox (iii) has written that there are four categories of pet-owner relationships: the object-oriented relationship, in which the pet is seen as a novelty, or a decorative item; the utilitarian relationship, in which the animal is used to provide a specific benefit to humans, such as being a guard dog; and the need-dependency relationship, in which the animal satisfies the human’s needs for companionship. The final category is the actualizing relationship, in which the person’s relationship with the animal is fully equal and based on mutual respect.

Pet ownership is also gendered. Sociologist Michael Ramirez (iv) shows how pet guardians use gender norms to choose their companion animals, to describe their pets’ behaviors, and they use their pets to display their own gender identities.

For example, the men Ramirez surveyed reported that they consider dogs to be a more “masculine” animal than cats, and both men and women explain their pets’ behavior in terms of their sex—female animals were said to “flirt” and women were more likely to describe their pets in more feminine terms, while men were more likely to describe theirs in more masculine terms.

In addition, men were more likely to play and roughhouse with their dogs, while women were more likely to kiss and hug them. Gender roles and expectations, then, shape not only how owners see their companion animals, but how they relate to them as well.

Development of Humane Attitudes through Pets

Pets, it is clear, do things. They can influence our behavior, affect our emotions, and even impact our health. What is also clear from recent research is that they influence our attitudes—about and towards other animals, and towards other people.

Research has shown that there are, broadly, five sets of factors to be related to attitudes towards animals: personality, political and religious affiliation, social status (class, age, gender, education, income, employment, ethnicity), environmental attitudes, and current animal-related experiences and practices.

Of the final factor, living with a companion animal is the most common way in which attitudes towards other animals are shaped. Those people who live with animals as companions may have a more positive attitude towards other animals, while those whose current animal experiences tend to be exploitative will have negative attitudes.

Attitudes towards pets in adulthood are correlated positively with having had family pets as children, and having had important pets. When those childhood experiences were good, the adults continued to like and want pets as adults.

These studies also show a positive correlation between pet-keeping as children and humane attitudes as adults, including vegetarianism, donating to animal charities, and belonging to animal welfare organizations. It seems clear that living with companion animals plays at least some part in our attitudes towards other animals, and, perhaps, towards other people.

A number of recent studies points to a correlation between positive attitudes toward companion animals and a more humane attitude toward other animals, and even some very preliminary studies are showing there is a link between positive attitudes toward animals and a more compassionate attitude toward people.

Anthropologists James Serpell and Elizabeth Paul (v) trace the evolution of animal keeping in the West and its association with attitudes toward fellow humans. They point out, for example, that starting in the seventeenth century, many of the most enlightened humanitarians had an affinity for animals, and that scholars and philosophers dating back to the ancient Greeks thought eliminating violence toward animals would make humans more peaceful.

We also know that abolitionists and animal rights activists were often the same people. So there appears to be at least a correlation between affinity towards animals and social justice.

In fact, as we have seen, during the nineteenth centuries when the commercial pet industry began to develop, many saw animal companionship as a way to cultivate virtues like kindness and self-control in young people, and the humane education movement takes as its central premise the idea that childhood pet-keeping can be used as a springboard to teach children empathy towards other animals.

In 1882, George Angell, founder of the Massachusetts SPCA, created the Bands of Mercy, which were after school clubs where children met, learned about animals, prayed, and testified about the animals that they had helped. Currently, eleven states have laws mandating that public schools teach some form of humane education, acknowledging the importance of having young people learn about kindness towards animals.

Today, some scholars (vi) think that living with animals may in fact teach empathy and compassion—towards animals and people. However, at least one recent study challenges this notion, finding evidence that living with animals is not correlated with empathy and that living with cats is, in fact, negatively correlated.

One last point to consider is that pets occupy a unique position in human society—as cultural theorist Erica Fudge points out, “a pet is a pet first, an animal second” (p. 32)viii.

In other words, we love animals, but we really love pets.

i Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

ii Sanders, C. (1999). Understanding dogs: Living and working with canine companions. Temple Univ Pr.

iii Fox, M. W. (1979). The values and uses of pets. The Handbook of Animal Welfare: Biomedical, Psychological, and Ecological Aspects of Pet Problems and Control. New York: Garland STPM.

iv Ramirez, M. (2006). “My Dog’s Just Like Me”: Dog Ownership as a Gender Display. Symbolic Interaction, 29(3), 373-391.

v Serpell, J. A., & Paul, E. S. (2011). Pets in the Family: An Evolutionary. The Oxford handbook of evolutionary family psychology, 297.

vi Taylor, N., & Signal, T. D. (2005). Empathy and attitudes to animals. Anthrozoös, 18(1), 18-27; Ascione, F. R., & Weber, C. V. (1996). Children’s attitudes about the humane treatment of animals and empathy: One-year follow up of a school-based intervention. Anthrozoös, 9(4), 188-195; Melson, G. F. (2003). Child development and the human-companion animal bond. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(1), 31-39; Ascione, F. R. (1997). Humane education research: Evaluating efforts to encourage children’s kindness and caring toward animals. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 123(1), 57-78; Daly, B., & Suggs, S. (2010). Teachers’ experiences with humane education and animals in the elementary classroom: implications for empathy development. Journal of Moral Education, 39(1), 101-112.

vii Daly, B., & Morton, L. L. (2003). Children with pets do not show higher empathy: A challenge to current views. Anthrozoös, 16(4), 298-314.

viii Fudge, E. (2002). Perceiving animals: Humans and beasts in early modern English culture. University of Illinois Press.

©Animals & Society Institute

Comments

Post a Comment